Scandalous, groundbreaking, expressionistic, melodramatic, pornographic — all of these descriptors have been used to characterize the over a century long production history of Frank Wedekind’s first published play, “Spring Awakening” (1891). Even the critically acclaimed 2006 rock musical adaption of the play still shocked audiences for its frank depiction of teenage sexuality. Wedekind’s “Kindertragödie” explores the lives of adolescents in as they come to terms with their sexual awakening, and features scenes that address or blatantly depict rape, masturbation, child abuse, suicide, teenage pregnancy, abortion, and homosexuality. The play has faced censorship since its premier in 1906 all the way up until the 1960s, principally with the omission of the scenes involving homoerotic scenarios (Hensel, 1971). The choice to omit these scenes specifically is striking, and merits deeper critical analysis. In conjunction with consideration of the play’s production history, a queer literary analysis of Wedekind’s homoerotic characters and their interactions in the play can generate insight into how homosexuality functions within Wedekind’s dramatic schema.

The Wilhelmine Cultural Milieu and Wedekind’s Play

Thematically, Spring Awakening offers a powerful critique of the generational rift between morally purist and deeply religious 19th century German adults and their budding modernist-inclined children. The main characters are experiencing their personal societal reconfiguration as they transition into adolescence contemporaneously with the broader societal reconfigurations precipitated by the 1871 unification of Germany, a nation that formed under the authority of the conservative, Protestant Prussian monarchy. Within this overarching thematic mission and against this historical backdrop, the inclusion of scenes of homoerotic exploration performs an important though somewhat opaque role. Male homosexual intercourse was outlawed in Germany by the Prussian legal codes following unification with the infamous paragraph 175, and in the years that followed, the pathology of same-sex desire became a topic of contention and scrutiny among liberal activists and moral purists alike. Scholar John C. Fout highlights that for the latter group, social phenomena such as industrialization and women’s emancipation threatened traditional institutions of power, namely the church. The crisis of the erosion of masculine hegemony manifested itself in the purportedly effeminate and gender-subversive subject of the gay male (Fout, 1992).

Interestingly, Wedekind completed “Spring Awakening” in 1891 as the debates surrounding homosexuality in Germany were only beginning to expand into the public sphere. Despite the early scientific and psychiatric contributions to gay male pathology by Karl Ulrichs (1864-65) and Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1886), the liberal argument that homosexuality was a natural and that paragraph 175 should be struck down did not reach operational fruition until the founding of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in 1897 (Beachy, 2014). The publishing of Wedekind’s play (it would not be first performed for another decade and a half) thus came at a pivotal moment in Germany’s gay history; homosexuality was beginning to make progress in its ideation as a natural condition, but its condemnation was still used vehemently as a weapon in the cultural arsenal of the conservative political elite. Considering this historical juncture, let us examine the political and literary functions of the queer scenes in the play.

Queer Spatiality and Collective Homoerotics

In Act 3, Scene 4, masturbation becomes an act of collective homosocial performance. Set in a corridor of a reformatory, six boys play a game in which they must ejaculate onto a coin and whoever hits it with their semen first gets to keep it. At the literal climax of the game, the boys declare in unison, “Summa — summa cum laude!!” (Wedekind, 1891, 56)

This scene proved to be the most objectionable by censors, being omitted even in a 1965 production in London (Hensel, 1971). The particular spatiality Wedekind has chosen for this carnal amusement can be interpreted as queer in the sense of transient and non-hierarchical, given that within the confines of the reformatory, all societal stratification among the inmates outside of the gaze of their supervisors is rendered obsolete. Furthermore, we see the boys in a corridor, a space of passage and motion, rather than a courtyard or even dormitory where their sphere of existence would be more rigidly defined. Wedekind’s critique of the pedagogy of his era is presented both humorously and quite vulgarly with the group’s evocation of the highest academic honor right at the moment of orgasm, complete with double entendre. This scene is thus more than a mere shocking portrait of profane behavior in the reformatory; it is a tightly constructed summation of the author’s dramatic thesis. The freedom afforded the inmates after becoming categorically asocial precipitates their homoerotic experimentation, an experimentation that is translated into a battle for masculine prowess. This guise absolves each participant from their alleged degeneracy head-on; it is a prism crafted from the ignorance of the natural value of pleasure, whether it is achieved through heterosexual or homosexual means.

Queer Romance and Utopia

In Act 3, Scene 6, the penultimate scene of “Spring Awakening”, we see Hänschen Rilow and another classmate Ernst Röbel in a quasi-fantastical nature setting, resting there after working in a vineyard. Ultimately, the two share a kiss, Ernst declares his love for Hänschen, and Hänschen dismisses his love as a confused triviality of youth. Wedekind gives a very specific and expressive description of where the boys are:

Im Westen sinkt die Sonne hinter die Berggipfel. Helles Glockengeläute vom Tal herauf. —Hänschen Rilow und Ernst Röbel im höchstgelegenen Rebstück sich unter den überhängenden Felsen im welkenden Grase wälzend. (Wedekind, 1891, 61)

This richly described environment is in stark contrast to the other setting descriptions; no other scene is given such a specific and poetic portrayal. The wilting grass evokes the imminence of summer; the temporality is transient, the precariousness of the rocks destabilizing, and the setting sun invites the mystery and anonymity of night. The boys are given a private and dream-like space to explore their desires, a queer utopia guarded from the disapproval and ignorance of their oppressive village and school. They speak about visions of what they’ll be in the future, and Hänschen expresses his belief that the goal of leading a virtuous life is a fallacy. The kiss and Ernst’s subsequent declaration of love show he feels the same way, and although Hänschen doesn’t say he loves him back, his final line reads as a hopeful and comforting response to Ernst’s vulnerability.

Amidst the abundantly tragic action of the play, after a character has killed himself on stage, other characters have spoken about the abuses they suffer, and a female student is raped and sent to her death upon receiving an abortion, this scene arrives just before the ending, strikingly placid and joyful. In a stark contrast, Hänschen and Ernst’s homosexual intimacy is portrayed as romantic, whereas the other erotic scenes in the play are coercive. How can we understand Wedekind’s decision to include this hopeful, future-oriented queer oasis, both geographically and chronologically, within the relative desert of tragedy characterizing the rest of the play? Scholar Gabrielle Owen, in her queer analysis of adolescent literature, references theorist Lee Edelman in highlighting that queerness exists as antithetical to reproductive futurism, a hegemonic belief system that orients political action towards the progeny of future generations without regard to the lived experiences of the individual members of the generations themselves (Owen, 2015). The very state of being queer absolves oneself from the pressure of this futurity, for queer subjects inherently disturb the cycle of heteronormative conation. The pastoral utopia Wedekind has crafted for Hänschen and Ernst manifests a critique of this reproductive impulse, imaging a queer future liberated from the rigidity of lived reality.

A Queer Literary Futurity at the Fin de Siècle

To summarize, Wedekind’s presentation of homoerotic exploration in the play functions as a response to the hegemonic orthodoxy’s rejection of intrinsic human impulses, a rejection made at the expense of constructing an idealized citizenry, a social body that would be well-equipped to bolster the newly formed German nation (Taeger, 1998). Queerness for Wedekind is not merely an unnatural, socially-conditioned status; it is an innate desire obstructed by societal barriers. The ambiguous realm that Wedekind’s characters inhabit in “Spring Awakening” becomes a circus of libertine experimentation, and the resultant tragedies often stem not from the acts themselves, but from the imposed ignorance and coercion vested upon adolescents experiencing personal evolution in an uncertain and uncharted societal landscape. The radicalism of Wedekind’s writing proved difficult for the author and contributed to his delayed success as a playwright, evident in the aforementioned fifteen year gap between “Spring Awakening’s” publication and stage premier. We are thus given an anachronistic boon with Wedekind’s first masterpiece, a futuristic plea for how the world could and ought to be. In portraying homosexual desire and experimentation with nuance and depth, Wedekind defied the prevailing hegemonic prescription of heteronormativity and its demonization of homosexual proclivity, envisioning a society where natural erotic impulses are allowed to flourish and develop unencumbered by societal subjugation.

Bibliography

Beachy, Robert. 2014. Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. New York: Penguin Random House LLC.

Fout, John C. 1992. “Sexual Politics in Wilhelmine Germany: The Male Gender Crisis, Moral Purity, and Homophobia.” In Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 2 no. 3, 388-421. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Ham, Jennifer. 2007. ”Unlearning the Lesson: Wedekind, Nietszche, and Educational Reform at the Turn of the Century.“ In The Journal of Modern Language Association, Vol. 40 no. 1, 49-63. Chicago: Midwest Modern Language Association.

Jelavich, Peter. 1979. „Art and Mammon in Wilhelmine Germany: The Case of Frank Wedekind.“ Central European History, Vol. 12 No. 3, 203-236. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, Gabrielle. 2015. „Toward a Theory of Adolescence: Queer Disruptions in Representations of Adolescent Reading.“ In Jeunesse: Young People, Texts and Cultures, Vol. 7 no. 1, 110-134. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Taeger, Angela. 1998. „Homosexual Love Between ‚Degeneration of Human Material‘ and ‚Love of Mankind‘: Demographical Perspectives on Homosexuality in Nineteenth-Century Germany.“ In Queering the Canon: Defying Sights in German Literature and Culture, 20-35. Columbia, South Carolina, U.S.A.: Camden House.

Wedekind, Frank, 1891, with afterword by Georg Hensel, 1971. Frühlings Erwachen: Eine Kindertragödie. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam.

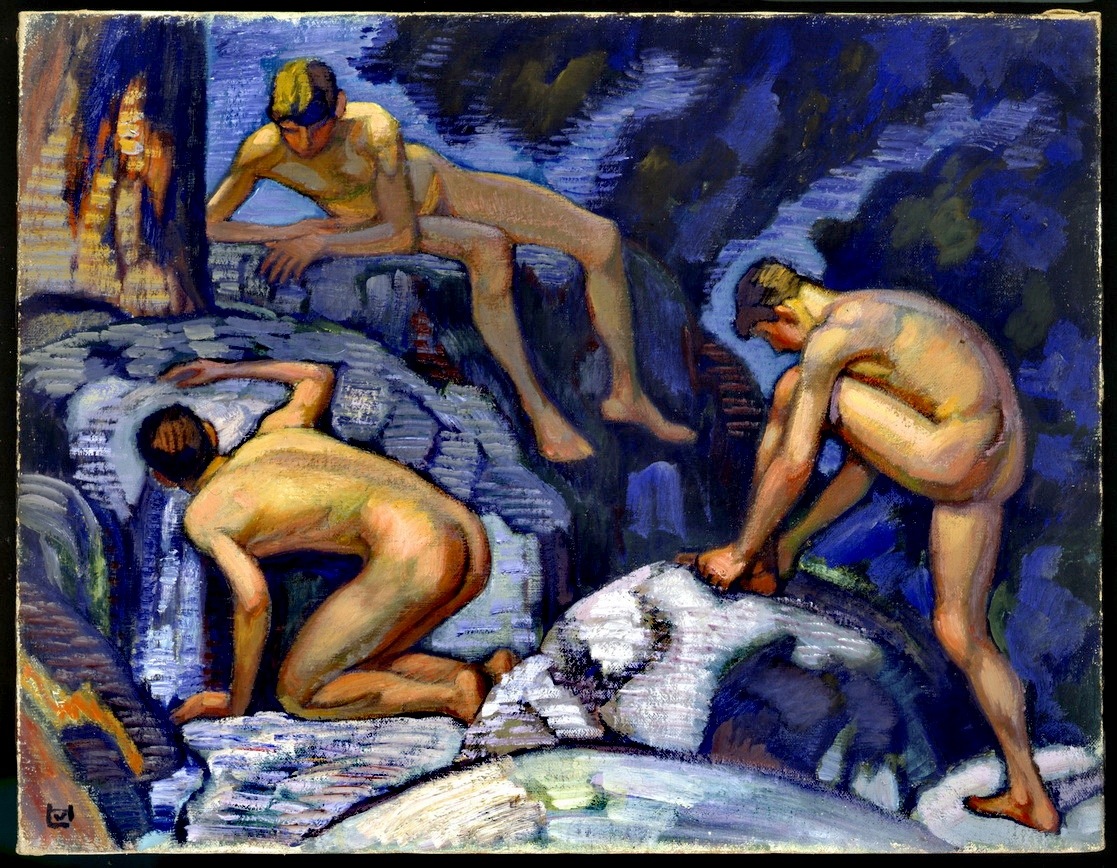

Title image

Die Quelle by Ludwig von Hofmann (1913), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ludwig_von_Hofmann,_Die_Quelle_(1913).jpg

Jason Goldman is a Master’s student in European History at the Humboldt University in Berlin. They researched ‘Jewish Homosexual Modernism in Germany and Mandatory Palestine from 1890 to 1940’ in Summer 2022 through the Humboldt Internship Program. Their research interests include German modernism and its international diffusion, queer analysis of the German literary canon, and historical sociology.