Hungary almost exclusively appears in the international news when it comes to the increasingly authoritarian rule of the Orbán government, which has been in place since 2010. The gender policies that have received international attention are limited to the pronatalist family policies, the potential limitation of reproductive rights , and the termination of gender studies master’s programs in 2018 – all framed by both the local and the international critical press as a cultural war against the homogenous group of ‘the Hungarian women’. In this blog post, which is based on empirical research that we conducted recently, we would like to draw attention to rarely discussed characteristics of Hungarian gender relations, namely how the structural dynamics of neoliberal transformation affect lower-middle-class and working-class women. Furthermore, we want to convey a more general understanding of factors shaping gender inequalities in the post-socialist context.

In December 2018, the Hungarian Parliament adopted a law on supplementary hours. It was quickly dubbed the ‘slave law’, as it allowed employers to order 400 hours of overtime per employee per year, which were to be paid out within three years’ time. After the law passed, protests erupted all over the country. Although public opposition faded away within two months, this scale of protests had never been seen before. Similar incidents, such as the erosion of the rule of law or freedom of the press, had not reached such widespread and long-lasting outrage in the previous years. While the law was in line with EU labor regulations (the neoliberal EU is not known for its protection from exploitation), it harshly affected large parts of the Hungarian population, especially those not in a position to negotiate with their employer on whether or not they were able to work extra hours, and those already struggling to make ends meet. In this context, it is important to keep in mind that the majority of people with the double burden of performing both paid and unpaid labor in different life stages are women. To shed light on these gendered aspects, we carried out a research project, the results of which were published in Hungarian in 2018 and in English in 2019.

Exploitation and the Crisis of Care

In the research project that was commissioned by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in 2017, we aimed to identify the difficulties confronting women in everyday life and how they formulated these issues. The project utilized six all-women focus groups throughout the country, three of which consisted of women with vocational school qualification at most and lower societal status, who are rarely the subject of sociological studies in Hungary. We also conducted a national survey involving 1,000 participants, both male and female, to find out how widespread the identified problems were, the connections between the different aspects as well as men’s perceptions. Additionally, we wanted to examine how gender relations were reflected in women’s narratives, and whether or not this corresponded to the discourse of the Hungarian government or of progressive actors trying to appropriate their voices. We used a mixed-method approach. In order to shed light on the hidden discursive structures, we thematically coded the relevant segments and applied a theme analysis on the transcripts of the focus groups. We then combined our results with the outcome of the representative survey.

Not surprisingly, the issues addressed in the focus group interviews (conducted in October 2017) were not the ones present in the culture war waged by the government (and in turn inadvertently supported by the reactive response of the opposition). Not once was the supposed threat of the ‘gender lobby’ mentioned. The migration crisis that has dominated public discourse since 2015 was referred to only once or twice. Instead, financial despair, low wages and disastrous working conditions, experiences of the housing crisis, the growing burden of elderly care, the state of the education and health care system, and mass emigration from the country dominated the narratives of the women.

One of the most striking results was the expression of despair when women described the field of paid labor: Terms such as “exploitation” and “slavery” expressed the level of tension these women experienced when describing their working conditions as seen in the following exchange.

Respondent 1.: Sick-leave… it doesn’t even exist anymore.

Respondent 2.: Certainly, there is, but I can’t risk taking it, I work ill and such.

R1. (replies): And when you go back, someone is already sitting there in your place.

R2. (answers to the reply): And there is certainly slavery.

(translated excerpt from a focus group discussion among women above 45 years of age, having vocational school qualification at most and living in the capital, Budapest)

Their employers‘ lack of tolerance for care for children, the sick, and the elderly further exacerbated this situation. Experiences reflecting this were recounted many times during the focus group discussions. The extent of this phenomenon was further uncovered in the ensuing survey.

„The other thing is to find a solution for the supervision of parents. Once they get older, and we are employed full-time, or even have two full-time jobs, we should be caring for our parents, but we cannot because of our long shifts. Neither can we support them financially, when they are on meager pensions because we ourselves just about reach the minimum wage, on which we survive from one month to the next.”

(translated excerpt from a focus group discussion among women above 45 years of age and living in the Hungarian countryside)

These accounts are tell-tale signs for a neoliberal discourse because it portrays women’s labor market participation as a way both to increase the gross domestic product (GDP) and gender equality. Our results highlighted that these tensions go well beyond the common framing of them as ‘difficulties with work-life balance’. This narrative might be applicable to describe the lived experience of a tiny strata of middle- or upper-class, highly educated, and resourceful women. However, the majority of women are forced to neglect or even sacrifice their private and family life in order to make ends meet. The main concern of women is not how to escape home to do ‘meaningful’ (i.e. paid) work and ensure their financial independence, but rather, how to escape paid labor in order to be with their loved ones. This demonstrates the hollowness of liberal feminist claims, which equate paid labor and a labor market presence with women’s emancipation, while ignoring care issues.

No Demand for Change in Unequal Gender Relations

The national survey we conducted confirmed the results of the focus groups. The majority of the problems faced by women in Hungary are not perceived to be women’s issues as they are shared by men of the same class. In cases where women’s problems are recognized as such, the perception of these did not differ between men and women. Therefore, it is apparent that men do clearly see the burdens women face – and arguing that women do not see their oppression is rather misplaced: Men and women realize that they face partly the same, partly different challenges of the same exploitative system. While women are overburdened with care work in addition to paid work, men are overburdened with two to three jobs to make a living for their family. As mentioned by us before, this is partly due to the constellation of family units in Eastern Europe in which women tend to be economically dependent on their (male) partner. Additionally, family is an important source of community and, potentially resourceful networks. Thus, it is useful to suggest that these women rebel against their husbands only if there are satisfactory measures set up by the state to help them: decent wages in the labor market, affordable housing, effective support or shelter for women facing intimate partner violence. These circumstances may explain the success of the recent family policy measures, such as preferential family-starting credits or lower family taxation, especially with those whose only resource is family.

No Help in Sight

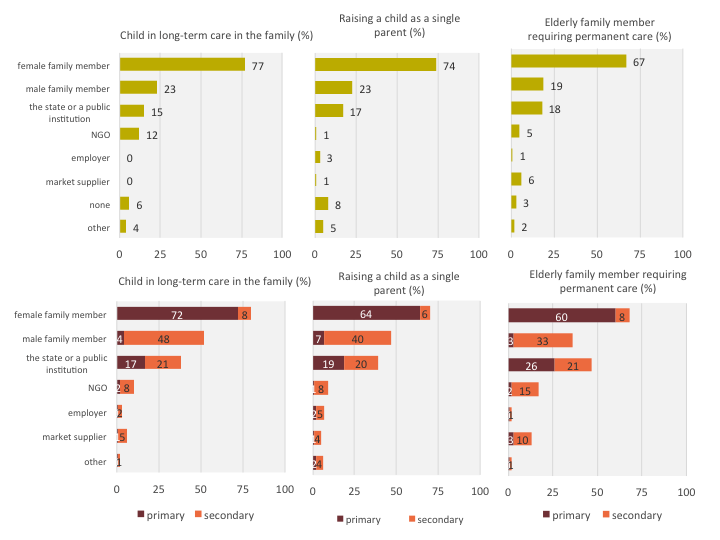

A devastating finding of the focus group interviews is that, as a consequence of this difficult situation, these women do not expect anything from anyone: the municipality, the state, the employer, the civil society. They can only rely on the small community that is their family. Furthermore, in part due to the lack of high-quality and accessible professional care services, families rely almost entirely on the care work of the female family members. As the figure below illustrates, a massive majority of our respondents face care-related issues, like childcare, care for grandchildren or elderly care responsibilities, in their families. They reported that female family members cared for the person in need. In similar situations, respondents primarily expect female family members to do the care work.

Bar charts in first row: In your experience, who has helped in such a situation in the past?

(Those who have already experienced the particular situation in life in the past or are experiencing it now themselves or are witnessing it through a relative may provide more than one answer, ratio of mentions, %)

Bar charts in second row: Which of the following actors do you think should be primarily responsible for providing assistance? And which actor should be secondarily responsible? (all respondents, %)

Although it is true that on average men spend much less time doing household chores and childrearing activities than women, one needs to be cautious about campaigning only for individual solutions, like awareness-raising campaigns, sensitivity trainings, and individual conduct-focused projects that urge men to increase their participation in care work. When these topics came up during the focus group interviews, the women expressed that caring, nurturing, and running their households were their tasks. It may thus be concluded that before there is a safety net provided by the state or community, it is ineffective to mobilize or encourage these women to rebel and create change.

The Lived Realities of Men and Women

The biggest problem with the Hungarian government is not its pronatalist nature – this can still be regarded as being within a democratic framework. However, attempts at change will fail if the labor market policy, the lack of a care infrastructure, the role of men, and social security are not addressed. The government clearly does not want to ‘send women back to the kitchen’, but both to the kitchen and the workplace. Therefore, the question is: How can progressives, worried about the state of democracy and gender relations in Hungary, address the most pressing issues of Hungarian women and Hungarian families? The important issues are having a decent job that provides a living, finding time and resources (to care) for loved ones, and the structural change that is needed to address the extreme tension between paid work and care work. Individualist calls directed towards men to do more care work, simplistic narratives on an alleged cultural backlash, and imported discourses on ‘white heterosexual men attempting to remain in power’ will not be helpful in addressing the root of the problem. We need to go beyond, and work towards an agenda based on the lived reality of men and women in Hungary.

- This blogpost is based on our recent publication:

Gregor, Anikó & Kováts, Eszter (2019) Work – life: balance? Tensions between care and paid work in the lives of Hungarian women. in: socio.hu, Labour relations and employment policies in times of volatility: Special issue in English No. 7 (2019) December 2019. 91-115.

Anikó Gregor, PhD, is an assistant professor of sociology at University ELTE Budapest and current Research Fellow in the Academy in Exile program, at Freie Universität, Berlin.

Eszter Kováts is a PhD student in political science at University ELTE Budapest and currently a guest researcher with a DAAD scholarship at the ZtG, at Humboldt Universität. Until the end of 2019, including during the time of the above mentioned research project, she worked for the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Budapest.