When planning an academic conference on „Nature-Society Relations and the Global Environmental Crisis“, which focused on climate change and sustainability through intersectional theory and transdisciplinary gender studies, we, Suse Brettin and Meike Brückner, did not anticipate visa issues. However, one of our invited speakers had their visa refused unexpectedly.

The panel discussion „Finding Common Ground to Address the Climate Crisis and Gender Injustice with Activists“ took place during the conference in May 2023. It explored how gender, age, race, and ethnicity intersect in activism, recognizing that the climate crisis impacts people differently. Originally, four panelists with backgrounds in different areas of activism shared their perspectives.

Before the conference, panelist Kai Njeri from Kenya was denied entry to Germany, despite having their visa application costs covered – underscoring colonial continuities and the impact of border regimes. We talked with them about their activism later via Zoom. This interview gathers Kai’s thoughts on the main themes from the panel discussion.

In preparation for our discussion, we requested a photo related to your activism or yourself. Could you introduce yourself and your activism using this image? What are the goals of your activism, and how are they connected to climate (in)justice?

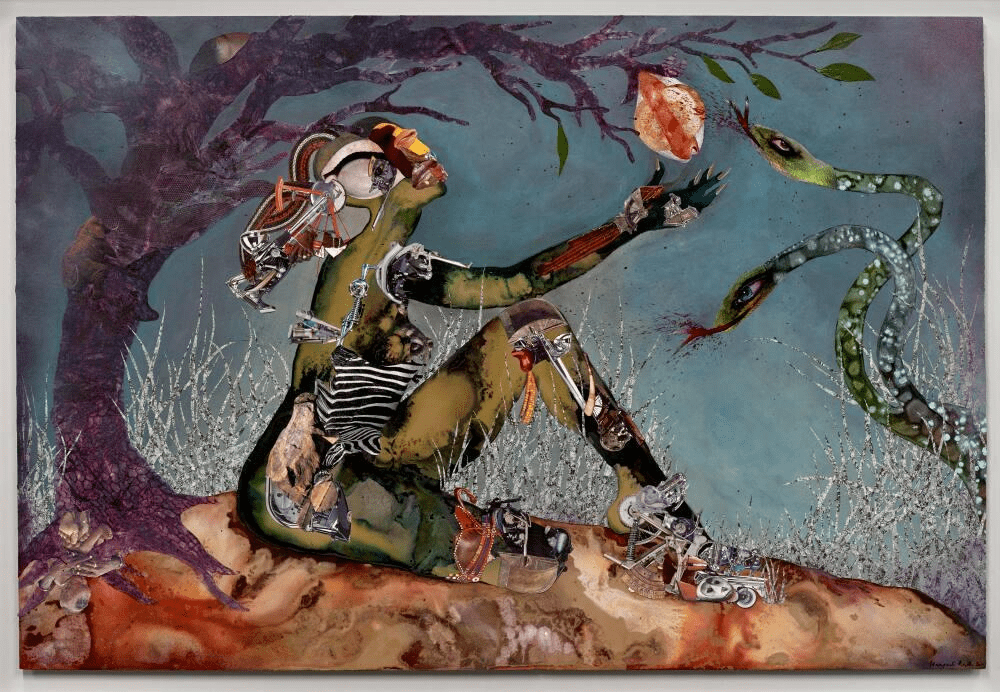

Kai Njeri: The photo montage I sent you – Wangechi Mutu’s Forbidden Fruit picker – tells a familiar story in a way whose textures resonate with me as an adult of different faiths living, in many ways, a life to the left of the faith of my childhood. In what is referred to as ‘the fall of humanity,’ the female character, Eve, is said to have fallen for the snake’s wise musings and ate of a fruit that was forbidden. This story goes on to define the relationship between woman and procreation, the power dynamics between woman and man, humans and our animal kin.

I chose this magnificent piece of art because it adds grotesque textures to this story, visually. It touches a place within that refuses to rest with the story as it was told to me and has continued to be told. This consistent state of unrest about the feminine inspires my work. I am deeply invested in the healing of and healing power of the feminine, exploring what medicine it holds for us as we address the metacrisis and the role it plays in recalibrating humanity’s trajectory.

I refer to myself as a regenerative systems thinker and designer. My approach is systemic and multidisciplinary; a meta-response to the metacrisis. My goal is simple: thrive! In all of my work, I attempt to answer the question of what it takes for our planet to thrive, sum and parts.

What specific consequences does climate inequality have in your field of activism?

Kai Njeri: The smallholder farmer whose livelihood depends on seasonal rhythms will be affected differently from the large-scale farmer with an intricate irrigation system, for instance. Economic status determines how buffered one can be from the impacts of climate change. Communities where the woman is not allowed to, for cultural reasons, earn income or contribute to the household in tangible ways or, even worse, is expected to contribute through farming, have been found to have an increased rate of gender-based violence as the seasons grow more and more arrhythmic.

Women’s voices and those of other discriminated groups often lead grassroots environmental movements. What role do gender-based or feminist claims play in your activism? How do feminist and ecological goals intersect in your efforts, and is there a common thread?

Kai Njeri: To answer this question, I have to let you in on my perspective of the feminine as it travels through humanity, our more than human kin and our planet. I will begin by taking us back to the Forbidden Fruit Picker.

Somewhere in the evolution of humanity’s collective psyche, the feminine became something to fear and, therefore, something to fight and oppress. This shows up in many religious texts: the gendered nature of social structures, the opportunities available to women, the extractionism and this strange deep sense of entitlement to the feminine that modern culture has. Now, for a species whose evolutionary pattern is this, don’t you think it dangerous that the earth is considered female/feminine? We talk of ‘Mama Earth’, Gaia, and even for the Gikuyu people, my people, the earth is Ngai’s female counterpart. While this may have been a quality that evoked care centuries ago, in the age of capitalism it is different; for consumerism and patriarchy to regard the earth as female/feminine has been detrimental. She, too, is now burdened with the curse of the forbidden fruit picker.

The common thread is the oppression of and extraction from all that is female/woman/feminine. In my work, I regard the earth as a sister. One to hold hands with in seeking regenerative solutions to climate change and humanity’s gender issues. All oppression is connected. For the feminine/women, for us all, to be free from these oppressive forces, the earth has to be and vice versa. In my work, I find separating the two quite difficult. Ecofeminism.

Do you experience resistance when you actively include awareness of categories such as gender, age, race etc. in your activism? From whom – within your groups or from outside/from society?

Kai Njeri: Totally! I was told not too long ago by someone in my close circles that patriarchy is not real. Most of my work focusses on girls, women and queer folk of all ages so resistance is both from within as it is external, especially in places where religion is influential.

I also believe that these times necessitate the invocation of grace in unifying our efforts as a species across the different lines of separation. This sentiment, as life-bound as it may sound, has landed me in a lot of trouble both within and outside of my groups. There is safety in shared codes. To ask that we expand these codes across, cultures, subcultures, privilege and oppression can come off as naïve and even rudely bold.

How important is cooperation in what you do? Do you have an example of a surprising (fruitful) association? What collaborations and bridges would like to build?

Kai Njeri: As important and necessary as fungi, critters and sunshine are to my favorite moringa tree! We do nothing alone. After a Jah9 concert in 2016, I met a man with whom I spoke for hours about food, seeds, soil and the gift of ancestral wisdom. Had I known we would go on to establish many thriving regenerative gardens together I might have taken record of my surroundings a bit more!

From the more obvious resource-mobilizing collaborations to the less obvious ones such as with innovative textile industry folks, there are many questions seeking responses. I would like to collaborate with a textile manufacturer producing biodegradable and light non-absorbent fabric. This would enable us to replace the only plastic component in the re-usable sanitary kits we distribute to girls and women in vulnerable contexts in East Africa.

A dream I hold dear is to host/be part of a project that is a collaboration of artists, academia, birthwork, seed sovereignty and

biodiversity restoration.

What role does academia play in your activism? Do you see a gap between “academic goals” and “activist goals”?

Kai Njeri: Mostly the role of providing data for now, and a lot of the questions I ask have little if any data on them, so there is work to do.

Yes. Activism insensitive to emergence does not get much done. It is in the very nature of action; and therefore activism, to be present to prevailing realities. It, as well, cannot get caught in the trap of imagined potentialities for their own sake. Academia can and this is a gift to activism. It has, however, been one of the many points of disconnect.

Academia, as is structured in these our contemporary times, can be rigid and requiring of processes with multiple steps and layers to get anything done. While this is, to its extent, valid, it easily becomes the place where activism’s fire goes to die.

Now, that said, academia can offer activism the space to grow roots, proofread itself and strategize, when it dares to keep up. Just as activism offers academia contextualization, system updates and diversified perspectives. There are many great opportunities for synergy.

From your experience, which areas of lived reality, of struggles, should get more academic attention?

Kai Njeri: All of women’s health. All of it. The connection between women’s health and planetary health. The connection between women’s health and the thriving of social and economic systems and structures.

What kind of collaboration would you need or want from academia?

Kai Njeri: Right now the area of my work that could do with a good strong academic eye is the intersection of nutrition, menstrual health, maternal health and women’s mental health. I would like to explore the impact it would have on our food systems and the restoration of our planet’s biodiversity if we centered women’s health as a way to determine and keep track of humanity’s and planetary thrive.

References for title image

Forbidden Fruit Picker by Wangechi Mutu, 2015. Digital MFAH Collection

Provenance of the artist; [Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2015]; purchased by MFAH, 2016.

Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Kainyu Njeri is a regenerative systems thinker and designer from Kenya whose work cuts across the fields of food and seed sovereignty, regenerative economics and education, women’s health and gender reconciliation. Their poetic pen cannot be helped, and for it, they are also a published author.

Suse Brettin is a PhD researcher in the field of Gender and Globalization at HU Berlin. As part of her doctorate, she is working on a feminist perspective on practices of care in the context of agricultural production. Her work also focuses on social relations to nature in the areas of agriculture, food, and water as well as the analysis of alternative value chains and food networks.

Meike Brückner is a postdoctoral researcher at the Division of Gender and Globalization at HU Berlin, where she researches and teaches on the practice and politics of food and agriculture. Her work focuses on human-nature relations, community-based agri-food systems, digitalization and sustainability and qualitative methodologies. She completed her PhD on biodiversity, local crops and food sovereignty in Kenya.