Many people assume that queer rights movements are primarily about acceptance or visibility. But this perspective risks reducing queerness to a plea for recognition within the boundaries of a cisnormative world. I want to suggest something else: that trans materialism – as a theory, a framework, and a lived practice – is not merely an add-on to existing social structures. It challenges the very foundations of a gendered society. We’re not asking to fit in; we’re showing that the whole system needs rethinking. And we’re living this challenge every day, through our bodies, our choices, our very existence.

Beyond Acceptance

What I want to focus on here is, in Jules Joanne Gleeson’s terms, called “the encounter” – those tedious moments where trans individuals are compelled to justify their existence to a cisnormative world; these encounters are also moments of identity formation. As Gleeson notes, much of a person’s transition is framed around “mastering the way they in particular will be perceived”. Trans existence becomes a series of performative acts to be read correctly by strangers – a constant struggle to accumulate enough “gendered determinations.”

A trans materialist utopia would refuse this framework entirely and take the “burden of transition” off the shoulders of trans people. Why must we contort ourselves to fit into a system that was never designed for us in the first place? The concept of “passing” is a trap because it reinforces the power of the cisgender gaze – I mean those exhausting efforts to blend in, to not draw attention; in my case, to be read as a cis woman for safety and convenience. As if there’s only one way to be a woman. It forces trans individuals to become complicit in their own oppression. As Gleeson points out, the “deep stealth” dream – where a trans person is indistinguishable from their cisgender counterparts – is the ultimate form of assimilation. Trans materialism rejects this. No “blending” into the bland cisgender society. No “Excuse me, how can we better conform to your cisgender expectations?” I think a trans materialist utopia is built on shatters. But not because it despises gender entirely; it is more about society than gender expressions. Trans materialism confronts arbitrary societal constructions of gender.

The Beard Dilemma

As a transfeminine person with a visible beard the “encounter” is important. The German cis-system provides insurance coverage for electrolysis, acknowledging my transition, yet my choice to keep my beard (or sometimes I am simply too tired or lazy to shave) challenges the medical idea of what it means to “transition.” I don’t pretend that strangers perceive me as a woman in our brief encounters. It does not matter to me. Or rather, I am a woman, beard and all.

But let me be honest – the encounter does matter, sometimes painfully so. There are days when I’m too exhausted to navigate the questions in strangers’ eyes, when I don’t want to be a walking gender studies lesson. The encounter matters when you’re buying groceries and just want to be invisible, when you’re tired and don’t have the energy to assert your womanhood against every raised eyebrow. My beard – now mostly gone, just stubble really – became a daily negotiation between authenticity and safety, between my comfort and others’ comprehension.

My progression in those encounters is not linear; it is cyclical. This beard growth cycle refuses the concept of linear transition. I am not moving from point A to point B; I am oscillating between them. Gender transition is becoming, with no fixed endpoint – and this terrifies those who need fixed categories.

This is why trans circles matter so profoundly. As Gleeson highlights, they provide “a context or space for the articulation of new language, lifestyle developments, and culture.” In these spaces, we create our own meanings. Consider the radical potential in C. Jacob Hale’s (1997) description of leatherdyke communities, where bodies are “retooled” and “recoded” (p. 228). Here, a “vagina” becomes a “manhole” or “boyhole” – not as denial, but as creative resistance against cisnormative categorizations.

Trans materialism is not an abstract theory, it is flesh. The transition is The Body. As Zenju Earthlyn Manuel (2015) reminds us, we perceive life through our bodies. When certain bodies are marked as wrong, we understand our lives through that marking. Every trans person navigating public space knows this viscerally. Without the cis system’s rigid categories, there would be no need to mark some transitions as exceptions. We all change. Trans people just refuse to pretend otherwise.

Unfinished Bodies, Unfinished Revolution

Trans materialism cannot stop at language or personal transformation. It demands that society itself be fundamentally transformed by trans experiences, not merely accommodate them. This isn’t about creating a genderless utopia, but about embracing proliferation and flux as the natural state of all existence. As Gleeson reminds us, “We have made the best of our proletarianized existence, but we have yet to escape it.” The challenge is to move beyond survival, beyond creating underground refuges from cisnormative society. Trans materialism remains deliberately unfinished. Its power lies in continuously disrupting our assumptions about gender, identity, and what life could become. This is the unfinished revolution of trans materialism, and it is really messy.

Literature

Hale, C. Jacob. “Leatherdyke Boys and Their Daddies: How to Have Sex without Women or Men.”Social Text, Nr. 52/53 (1997): 223–36.

Manuel, Zenju Earthlyn. The Way of Tenderness: Awakening through Race, Sexuality, and Gender. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2015.

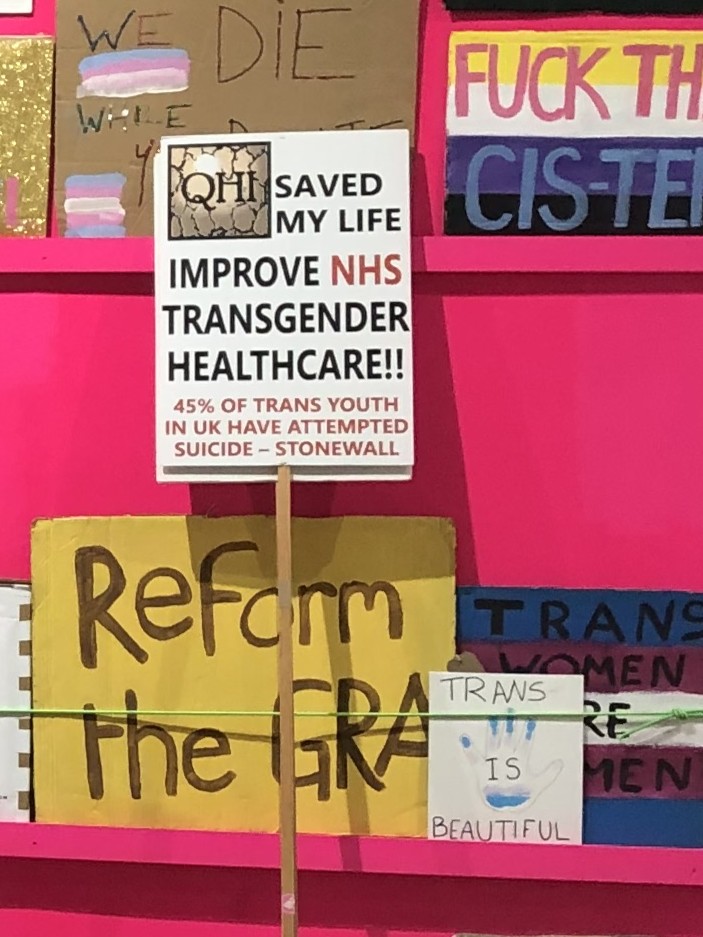

Title image (copyright Alaida Hobbing, edited by Genderblog Redaktion): Here the discussion invites to participate. The photo shows a close view at the “Transcestry” exhibition at the Museum of Transology in London, United Kingdom. It is the national trans archive in the United Kingdom.

Misha Komarova (she/her) is completing her anthropology and philosophy degree while working as a legal advisor for queer migrants in Berlin. She writes about trans embodiment from the intersection of theory and lived experience. Her work explores how bodies resist categorization whether facing border agents or bathroom politics.