The East German women’s movement remains an overlooked chapter of the history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). In fact, a history of the East German women’s movement is difficult to find in both the scholarship of the GDR and European feminist history more broadly. This is inconsistent with the plethora of archival evidence of the movement available. Women’s role in underground groups during socialism and in the 1989 protests remains a local story that is yet to cross into national commemorative efforts or broader histories of the GDR, particularly in the anglophone sphere. This blog post will theorize some of the reasons why the movement has been forgotten in feminist history and point to some recent scholarship that has started the process of rectifying this disservice to East German feminist activists.

Forgetting the East German Women’s Movement

The East German women’s movement has been a topic that scholars are reluctant to investigate and to date has been explored only in fragments. In her 2022 book, historian Jane Freeland questioned:

„The absence of East Germany in the history of feminism is particularly striking at a time when global, transnational, and postcolonial histories have revealed the instability of supposedly universal categories of liberalism, democracy and feminism, and queried the centrality of national boundaries. Why then have historians been so reluctant to study the history of East German feminism?“

The answer, I would argue, is that the social and political marginalization of East German women after the fall of socialism also translated into a minimization of their activities in studies of German reunification. When the women’s movement is mentioned in historical research, it is often equated with the Independent Women’s Association (UFV), an umbrella organization of East German women’s groups which joined a coalition with the Greens Party. This misconception frames the movement around one group’s activities in 1989–1990 and their subsequent electoral defeat in March 1990.

Although the UFV played an important role in garnering support for women’s rights during the roundtable discussions, a UFV-centric narrative overlooks the role the illegal women’s movement played in both the peace and dissident movements under socialism and during the Wende. Consequently, a narrative of (electoral) failure clouds the history of the UFV and in turn the history of the East German women’s movement, with German unity often serving as a convenient end point for this history.

This narrative disregards the activities of East German activists in the early 1990s, such as campaigning for better access to abortion and the emerging women’s shelter movement that was spearheaded by key activists of the movement. The UFV’s electoral failure and the neglect of other achievements of East German feminist activists in the scholarship feed into the stereotype of East German women as the “losers of German unity.” Such stereotypes impede nuanced studies on both GDR women and the women’s movement: a twofold disservice to these political actors, skewing historical reality by reducing an entire movement to one organization and its ultimate downfall.

Remembering the East German Women’s Movement

During the early 1990s Samirah Kenawi documented the existence of ‘non-state women’s groups’ in the GDR – ones typically concerned with a single issue (i.e., pacifism, lesbian rights, support for single mothers) – from the late 1970s onwards. The expansive collection of documents – consisting of flyers, meeting minutes and much more – is now housed in the Grauzone Archiv in the Robert Havemann Gesellschaft.

Using this source base among others (i.e. MONAliesA), Jessica Bock’s PhD thesis on the women’s movement in Leipzig is an impressive and detailed study into the extent to which the Leipzig women’s groups were constructed out of pre-existing networks (those traced in Kenawi’s corpus) and the extent to which the women’s groups that formed in 1989 were new to feminist discourse. Bock utilized the archival evidence as well as oral history interviews to reconstruct the history. The merit of her work lies in the richness of her study’s timeline of 1980 to 2000, which serves as a correction to earlier studies that anchor the women’s movement around 1989–1990. This trend in the scholarship was due to scholars’ motivation to uncover how socialism collapsed so rapidly and how this impacted women and their rights (see Barbara Einhorn Cinderella Goes to Market), plus the source base for this history was not yet archived in the early 1990s.

Historians of East German women’s history have a plethora of available evidence and it is hoped that in the next few years more research will be produced both in English and German. That is certainly the aim of my doctoral research. I have conducted ten interviews with former East German feminist activists from Erfurt, Weimar, Dresden, Leipzig, and East Berlin while I have been a visiting researcher at the ZtG. One of the central aims of my research is to decentralize Berlin from dominating the narrative of the East German women’s movement, producing a more accurate representation of the regional variety of the movement. It is hoped that my analysis of the interviews alongside the archival record will serve to diversify the ways in which we conceptualize the East German women’s movement, East German feminist ideology, its legacies, and how women now reflect upon their lives in the GDR after over thirty years in a liberal democratic order.

I look forward to sharing more of my research with the ZtG, upon completion of my doctorate.

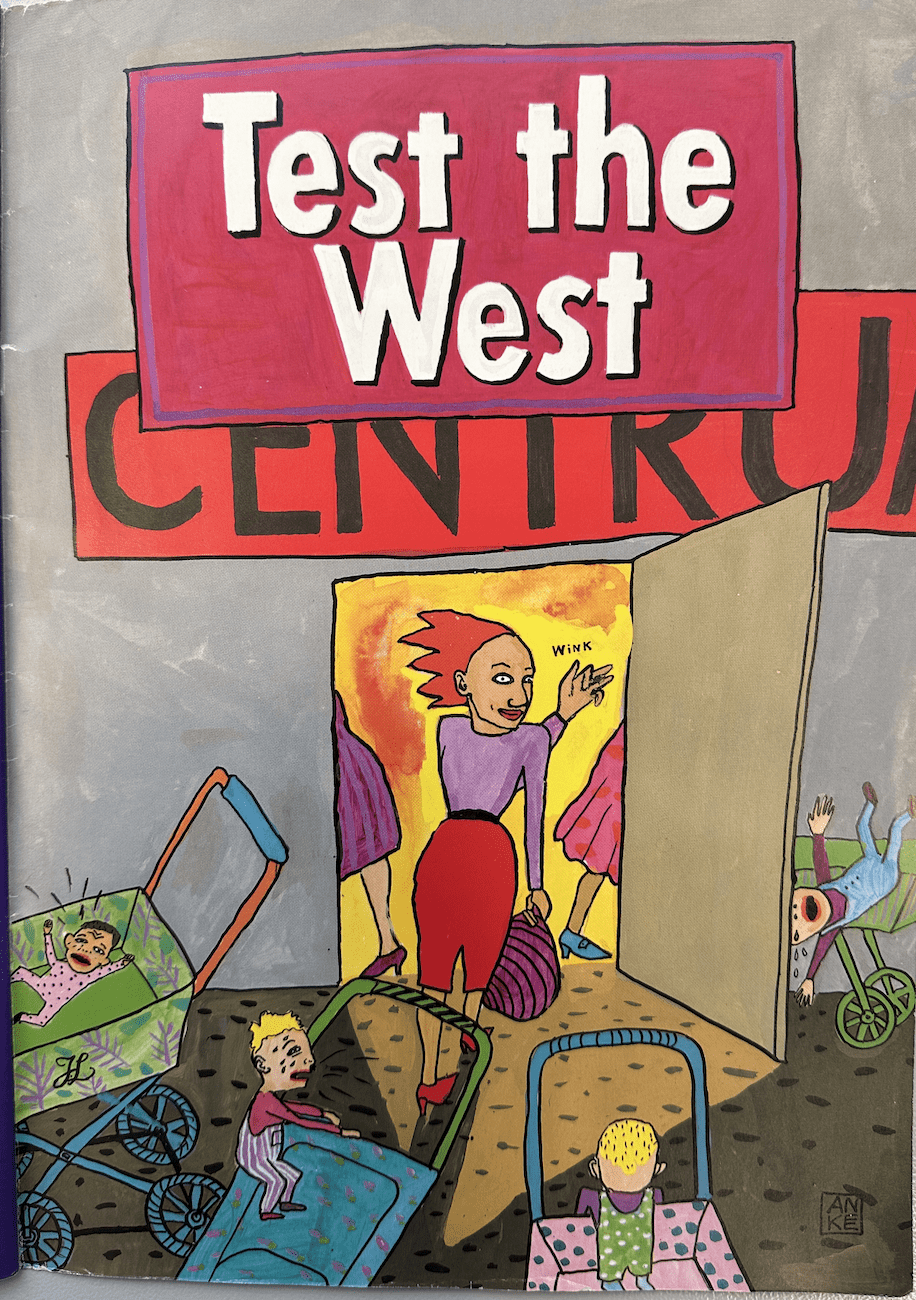

Reference for Title Image

Berlin, Protest gegen § 218, am Checkpoint Charlie, 29. September 1990, photograph by Peer Grimm, located at Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1990-0929-006

Kate R. Stanton is a researcher of East German women’s history during the collapse of socialism. She holds a Bachelor of Art (Languages) (Honours) and a Master of Teaching from the University of Sydney as well as a Master of Studies in Modern European History from Merton College, Oxford. She is now a John Roberts Doctoral Scholar at Merton College, Oxford, where she is writing an oral history of the East German women’s movement under the supervision of Professor Paul Betts and Dr Katherine Lebow. She has spent the 2023–2024 academic year as a Visiting Researcher at the Center for Transdisciplinary Gender Studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.